We are a coalition of individuals and groups proposing a Greenfield People’s Budget.

Greenfield’s Current Budget

A city’s budget represents much more than the simple allocation of resources. As Martin Luther King, Jr. noted half a century ago, a budget is also a moral document, one that demonstrates a community’s priorities and whose concerns it centers in decision-making. Greenfield’s current budget and budgeting process prioritize the interests of businesses and landlords and rely on the police to deal with the fallout from poverty, homelessness, addiction, and mental health crises.

Relying on police to handle social problems is ineffective, expensive, and dangerous. Greenfield can join the growing number of cities shifting budget priorities to reduce their reliance on police and move toward meeting the real needs of people in the community.

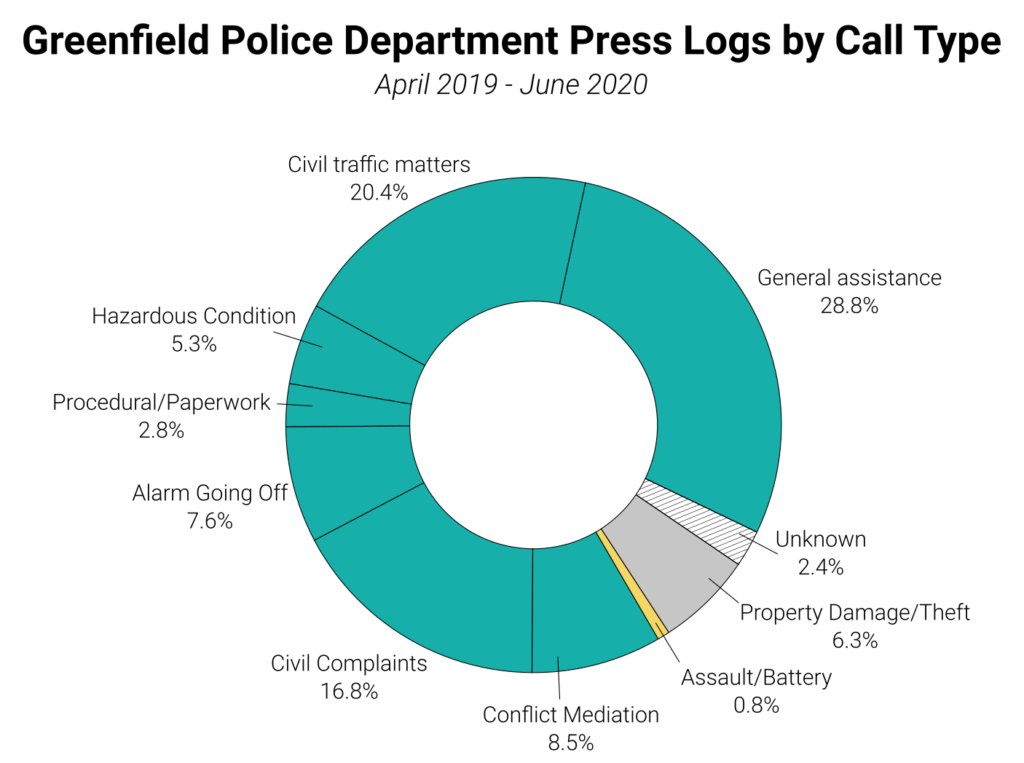

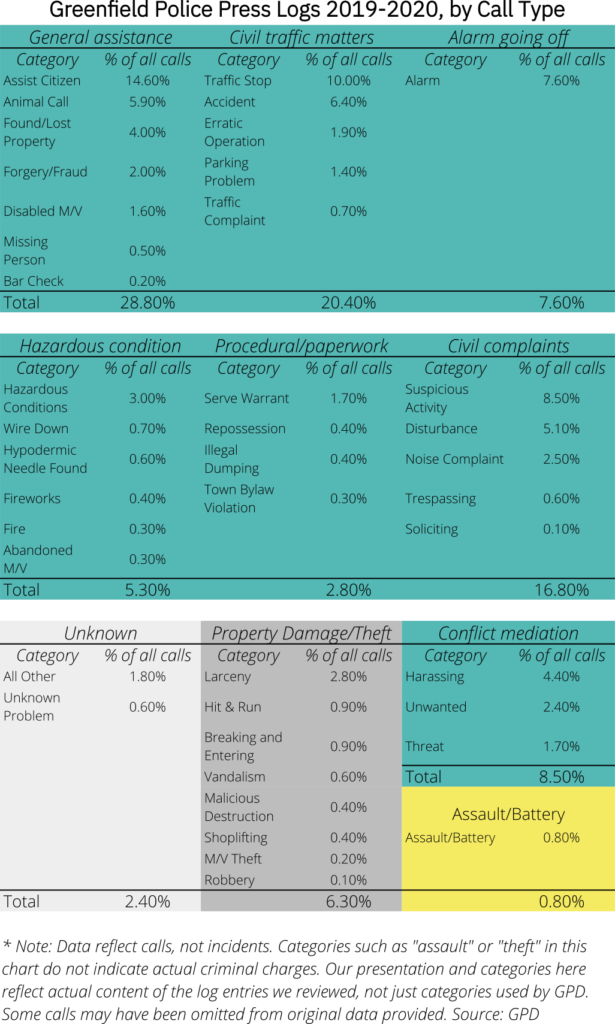

Myriad studies have shown that policing can’t solve social problems and causes extensive collateral damage in people’s lives. Reforming police departments through anti-discrimination trainings, body cameras, or “community policing” initiatives also fails to curtail police violence and racial profiling. Real safety simply does not come from controlling people with guns and jails. Rather, communities are safer when residents can meet their basic human needs without having to struggle. The Greenfield Police Department’s own data show that only a small portion of their caseload is responding to reports of crime. Rather, the majority of GPD work is responding to community requests for assistance (Fig. 1).1Less than 1% of police calls involve reports of assault or violence, and only about 6% of calls involve supposed property crimes—including many mundane items like “caller’s wife took his debit card,” “two large pumpkins stolen off porch,” and “BLM sign stolen.” Two thirds of police calls fall into categories including assistance for residents (28.8%; for example, “person flagged down officer to ask relationship advice”), traffic matters (20.4%), hazards (5.3%; “tree down”), and alarms randomly going off (7.6%). Complaints (17%) and disputes (9%) include many calls like people dancing in Energy Park after hours, “intoxicated person advised to go to bed,” and 102 calls (over one year) from the same address about a mental health issue.

What is a People’s Budget?

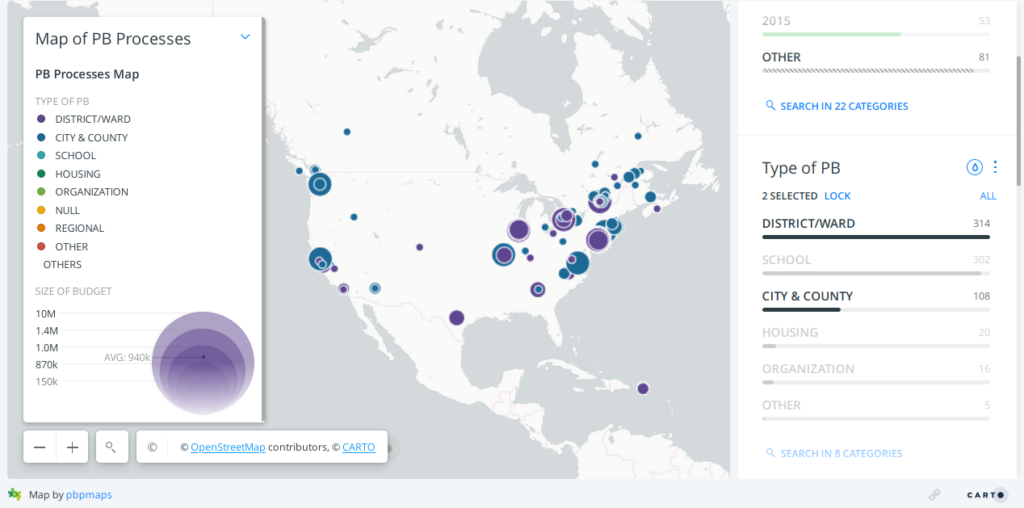

A People’s Budget is a city budget that residents write themselves through a process of participatory budgeting. Through neighborhood assemblies, surveys, visioning sessions, and votes, residents take the lead in shaping a budget that’s tailored to their community and its specific needs. Participatory budgeting has become an especially important tool for the many communities re-envisioning public safety and building new life-affirming city programs. Major cities like Seattle and Los Angeles, as well as smaller cities like Nashville and Sacramento, are using participatory budgeting to divest from traditional policing and re-invest those resources in programs and projects that address the root causes of social problems (e.g., housing-first initiatives and non-carceral mental health services) and create real safety (e.g., restorative justice programs and peer-led violence prevention and conflict resolution).

Participatory budgeting takes different forms in different cities. At its heart is always a series of public forums, where community members learn about the city budget and then talk together about local problems and how they think those problems should be addressed. This process makes space for people who are usually marginalized in electoral politics and in the municipal budgeting process (those who are most harmed by policing and prisons), acknowledging that people themselves are experts on their own lives and know well what they need in order to thrive. The participatory budgeting process is a “bottom-up” approach to meeting community needs and allocating resources, rather than the conventional “top-down” approach. This transformation is the basis for real safety and for successful city programs: the community writes a budget that responds to the needs they themselves identify, and city programs are democratically accountable to residents.

Greenfield suffers many of the same urgent social problems afflicting cities all over the country, problems only made worse by COVID-19 and the economic crisis it’s caused. A growing number of people have precarious housing situations or no housing at all, and landlords are serving evictions despite the formal CDC moratorium. Our existing social services are struggling to meet the mental health crisis, as well, and deaths by overdose have risen sharply. This desperate situation has overwhelmed our minimal social support systems. And, like every other community in America, Greenfield struggles with systemic racism, from race-correlated income inequality to racial disparities in arrests and criminal charges and school discipline. We must focus on proactive, human-centered solutions to these growing crises, not on ineffective punitive approaches.

How We Get a People’s Budget in Greenfield

All in all, there are six steps to getting the city to implement a People’s Budget:

First we take time to learn together what our community’s needs are and how other communities have met similar needs. This step takes shape through community teach-ins and other public events.

In this step, residents of Greenfield meet in public assemblies, organized by neighborhoods or by groups. Residents who can’t make it to the assemblies can participate through surveys and canvassing. Given what we’ve learned about our community and programs that have worked well in other places, we come up with ideas that make sense for our city.

The assemblies choose delegates to send to smaller meetings where big ideas get fleshed out into detailed proposals, with the help of professional planners and budget experts. We figure out how our ideas can become reality in Greenfield.

The public votes on the proposals that the smaller meetings make, as well as give more general feedback. In this way the community sets the priorities for which programs should be implemented.

The smaller meetings of delegates and experts gather again to write a budget for town programs that’s ready to be implemented by our government.

In the final step, we submit our People’s Budget to the City of Greenfield so it can be implemented.

In 2021, the Coalition for a Greenfield People’s Budget will conduct teach-ins, assemblies, and a community survey to begin the participatory budgeting process in Greenfield. With the residents of Greenfield we will re-imagine the city budget to meet the real needs of our community. This democratic process will create a Greenfield People’s Budget which we’ll deliver to the mayor and city council.

People in our community are suffering, and participatory budgeting is a powerful tool for addressing this suffering at its roots. Participatory budgeting offers a new way forward for our community, an opportunity to work together towards a future where everyone in Greenfield is able to live in safety, in comfort, and in engaged community with their neighbors.

Want to help out?

- Sign our petition and opt-in to updates.

- Share the petition with your friends and neighbors.

- Ask your organization to sign our petition.

- Sign up to volunteer and we’ll contact you about ways to get involved.

- Learn about participatory budgeting and community-led public safety through our frequently asked questions and resources & links.

- Follow our campaign updates on our blog.

References

- 1Less than 1% of police calls involve reports of assault or violence, and only about 6% of calls involve supposed property crimes—including many mundane items like “caller’s wife took his debit card,” “two large pumpkins stolen off porch,” and “BLM sign stolen.” Two thirds of police calls fall into categories including assistance for residents (28.8%; for example, “person flagged down officer to ask relationship advice”), traffic matters (20.4%), hazards (5.3%; “tree down”), and alarms randomly going off (7.6%). Complaints (17%) and disputes (9%) include many calls like people dancing in Energy Park after hours, “intoxicated person advised to go to bed,” and 102 calls (over one year) from the same address about a mental health issue.