Part 1: What It Is

A Community-Based Alternative to Policing

Why Civilian Mobile Crisis Response?

- Reduces police and criminal legal system contact for residents

- Provides the most needed services and compassionate care through the 911 system

- Builds trust and well-being

- Invests in community members with lived experience of oppression

- Builds community leadership and accountability

- More successful and less harmful than any other model

- Costs less than police response or social work response

Introduction

“Police spend an inordinate amount of time responding to 911 calls for service, even though most of these calls are unrelated to crimes in progress… All of this exhausts police resources and exposes countless people to avoidable criminal justice system contacts.” 1Neusteter, S. Rebecca, Maris Mapolski, Mawia Khogali, and Megan O’Toole. 2019. The 911 Call Processing System: A Review of the Literature as It Relates to Policing. Vera Institute of Justice. https://dataspace.princeton.edu/bitstream/88435/dsp01ms35tc556/1/911-call-processing-system-review-of-policing-literature.pdf

Police are expected to respond to almost every emergency, leading to high costs for cities and poor outcomes for many residents, most especially for people of color, low-income residents, and other marginalized groups. The national momentum towards police reform and expanded notions of public safety has focused attention on a number of alternative models for emergency response. This policy paper collects resources on the most successful model for mental and behavioral health crisis interventions: civilian mobile crisis response, a health-focused model that is entirely civilian and prioritizes support by peers.

Compared with civilian crisis response, other models come up short. Crisis Intervention Teams (CIT) training, for example, claims to give police officers increased knowledge and skills for dealing with personal crises, but the actual record shows that CIT training does not reduce arrests, use of force, or citizen injuries.2Rogers, Michael S., Dale E. McNiel, and Renée L. Binder. “Effectiveness of Police Crisis Intervention Training Programs.” Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online 49, no. 1 (March 1, 2021). https://doi.org/10.29158/JAAPL.003863-19 Officers proficient in CIT, some of them even CIT trainers, have killed people in mental distress numerous times.3Westervelt, Eric. “Mental Health And Police Violence: How Crisis Intervention Teams Are Failing.” All Things Considered, September 18, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/09/18/913229469/mental-health-and-police-violence-how-crisis-intervention-teams-are-failing Osborne, Deon. “Cop Who Shot Woman with Mental Illness Gives Training to Campus Police.” The Black Wall Street Times, April 28, 2021. https://theblackwallsttimes.com/2021/04/28/cop-who-shot-woman-with-mental-illness-gives-training-to-campus-police/ There is also growing support for “co-responder” or “ride-along” models, where clinicians join police officers to respond to mental health emergencies. Supporters claim these programs lead to marginally better outcomes, but the evidence shows that the presence of police causes a range of practical and ethical dilemmas for care providers.4Vakharia, Sheila P. “‘Social Workers Belong in Police Departments’ Is an Offensive Statement.” Filter (blog), June 10, 2020. https://filtermag.org/social-workers-police-departments/ James-Townes, Lori. “Why Social Workers Cannot Work With Police.” Slate Magazine, August 11, 2020. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2020/08/social-workers-police-collaborate.html Even more so, adding social workers to police response does not guarantee compassionate care, increase community trust, or rule out coercive outcomes.5Evens, Philip. “Social Control and Values in Social Work.” Probation 19, no. 1 (March 1, 1973): 9–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/026455057301900103 Survivors of coercive psychiatric care and even many social workers are opposed to co-response models,6Davidow, Sera, for the Wildflower Alliance. “Open letter to the Mayor of Northampton,” May 19, 2021. https://wildfloweralliance.org/open-letter-to-the-mayor-of-northampton/ Vakharia, Sheila P. “‘Social Workers Belong in Police Departments’ Is an Offensive Statement.” Filter (blog), June 10, 2020. https://filtermag.org/social-workers-police-departments/ James-Townes, Lori. “Why Social Workers Cannot Work With Police.” Slate Magazine, August 11, 2020. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2020/08/social-workers-police-collaborate.html yet law enforcement officials promote these programs because they sound progressive despite preserving or expanding police participation in non-criminal emergencies. CIT and co-response are not solutions, they’re “a workaround for a system that shouldn’t be sending law enforcement to a call.” 7Angela Kimball, national director of advocacy and public policy for the National Alliance on Mental Illness, quoted in Minyvonne Burke, “Policing Mental Health: Recent Deaths Highlight Concerns over Officer Response.” NBC News, May 16, 2021. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/policing-mental-health-recent-deaths-highlight-concerns-over-officer-response-n1266935

Civilian crisis response delivers real benefits for residents in crisis, for police departments, and for the broader community. Peer support workers combine lived experience and expert training to help people in crisis get the care they need in a manner they can trust, rejecting coercive and punitive approaches (such as involuntary hospitalization) in favor of therapeutic peer support practices. These emergency response programs are a way for cities to invest public dollars in building resources for community well-being and resilience, all while reducing people’s contact with the criminal legal system and the harmful life consequences that often come as a result of police interactions. Civilian models can also offer meaningful employment to community members who have survived and overcome significant life challenges. The model described below additionally delivers all of these benefits for a cost that is less than that of police-involved emergency response.

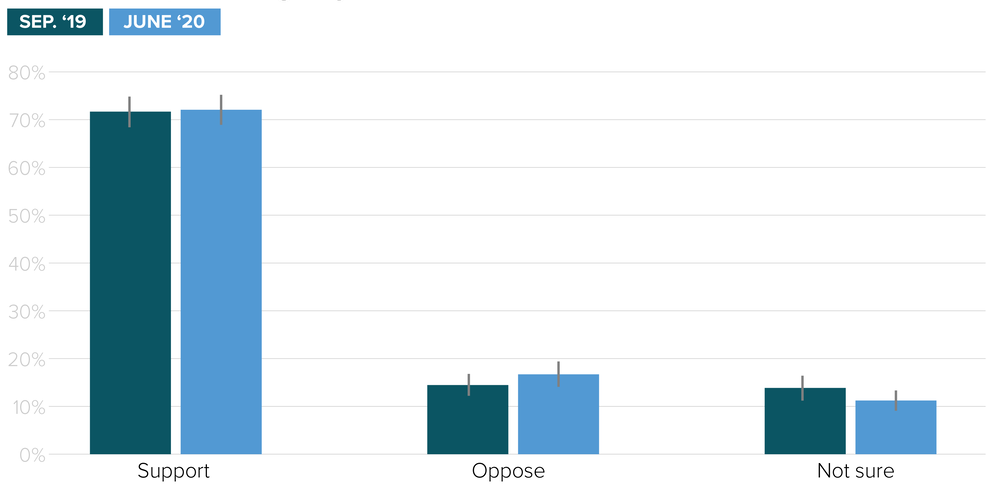

Poll: New First Responder Agency for Addiction & Mental Health

first responder agency for mental and behavioral health emergencies, even in polling months before the 2020 protests.8White, Mark. “Voters Want a Non-Police First Responder Agency for Addiction and Mental Health.” Data For Progress, June 11, 2020. https://www.dataforprogress.org/blog/6/11/voters-want-non-police-first-responders

Greenfield is ready for civilian crisis response.

We have a strong community of peer leaders, including members of the Wildflower Alliance and the RECOVER Project, who last year called on the city council to establish exactly this type of program. The first recommendation from their 2020 forum is:

“Community-led mental health, addiction, harm reduction, and crisis support, as well as support for youth in schools, and other social (DCF) and medical (ER) services that are decoupled from law enforcement, coercive/involuntary treatment, and punitive measures.”

Wildflower Alliance, RECOVER Project, and others9“Community Forum Recommendations,” shared with Greenfield councilors in December 2020

Many city residents want to help community members who are struggling, and they see that policing is not the solution. We have law enforcement partners in the Greenfield Police Department and the Franklin County Sheriff’s Office who have already demonstrated their interest in public health-based programs. State funding is available from various sources (Senator Comerford, and the Mass. Departments of Public Health and Mental Health), and civilian crisis response programs are eligible for funding under the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA).

We can benefit from the practical implementation advice made available by existing successful programs in similar places across the country, as well as the strong region-wide movement toward civilian public safety programs, including in the neighboring cities of Brattleboro, Northampton, and Amherst. As we grow our own peer crisis response program, we can even offer this crucial service to our neighbors across Franklin County, as well.

Let’s talk about how civilian crisis response can help make Greenfield a safe, thriving community for all of our neighbors.

Part 2: How It Works

Civilian mobile crisis response refers to a wide range of services that are designed to meet the needs of community members experiencing crises related to mental health, behavioral health, or substance use. These services are deployed through the 911 emergency call system or a similar parallel system. Civilian crisis response aims to reduce police involvement in crisis calls, instead providing community members with direct access to professionals and paraprofessionals who can address their needs without the risk of escalation, arrest, or further violence.

Similar programs exist that do not include peers, but programs are much more successful when they prioritize leadership and care by peer providers who share life experiences with the community members they serve. Peer leadership and consensus-based decision-making are the necessary building blocks for on-going community accountability, since these elements preserve a care-based ethos both during service provision and among staff themselves.10Tim Black, CAHOOTS, Interview with Northampton Policing Review Commission, March 10, 2021; Rachel Bromberg, Reach Out Response Network, Interview with NPRC, January 5, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a1VP-DsHEs0 Shared experience among staff and clients helps build trust and also leads to care that is more responsive, compassionate, encouraging, and inspiring, enabling residents in distress to reach better outcomes and maintain more commitment to on-going self-care.11Davidson, Larry, Chyrell Bell Amy, Kimberly Guy, and Rebecca Miller. “Peer Support among Persons with Severe Mental Illnesses: A Review of Evidence and Experience.” World Psychiatry 11, no. 2 (June 2012): 123–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.05.009

“Help isn’t help if it doesn’t help.”

Pat Deegan12Quoted by Sera Davidow for the Wildflower Alliance. “Open letter to the Mayor of Northampton,” May 19, 2021. https://wildfloweralliance.org/open-letter-to-the-mayor-of-northampton/

By contrast, negative contact with police (e.g. stops, arrests, incarceration) harms the well-being of the people involved. Research has documented a wide array of negative health outcomes from such interactions, including trauma, anxiety, psychological distress, worsening of chronic illnesses and substance-abuse conditions, and shortened life expectancy.13Sundaresh, Ram, Youngmin Yi, Brita Roy, Carley Riley, Christopher Wildeman, and Emily A. Wang. 2020. Exposure to the US Criminal Legal System and Well-Being: A 2018 Cross-Sectional Study. American Journal of Public Health 110: S116-S122. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305414 These harms are not experienced equally by all community members. People of color, low-income residents, and other marginalized groups have disproportionately experienced heavy police presence and unwanted contact with police, high rates of arrest, and harsh enforcement tactics. People in distress due to mental or behavioral health crises are also often treated like criminals and threats to public safety, subject to enforcement and coercive, punitive medical interventions.14Irwin, Amos, and Betsy Pearl. The Community Responder Model. Center for American Progress, October 2020. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/criminal-justice/reports/2020/10/28/492492/community-responder-model/ Camplain, Ricky, Carolyn Camplain, Robert T. Trotter II, George Pro, Samantha Sabo, Emery Eaves, Marie Peoples, and Julie A. Baldwin. 2020. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Drug- and Alcohol-Related Arrest Outcomes in a Southwest County From 2009 to 2018. American Journal of Public Health 110: S85-S92. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305409 Diverting non-violent emergency calls away from the police helps protect and build the well-being of community members while also alleviating the workload of the police department.

Yet as the communities most impacted by policing have made clear, reducing contact with police officers is not enough to guarantee compassionate care when you need it. Institutionalized social work and clinical models rely heavily on paternalistic and coercive interventions, collaborate with other harmful state institutions, and often have bad reputations with clients as a result. Peer-based care models instead draw on the wisdom and experience of survivors of state violence and psychiatric care. Peers “know what it is like to feel powerless over their own life,” in the words of the Wildflower Alliance.15Davidow, Sera, for the Wildflower Alliance. “Open letter to the Mayor of Northampton,” May 19, 2021. https://wildfloweralliance.org/open-letter-to-the-mayor-of-northampton/ Peer models acknowledge the trauma caused by institutionalized care and offer consensual interventions that respect the humanity and autonomy of people in distress. These therapeutic practices are highly successful and even recognized internationally by the WHO, but they remain chronically under-resourced and under-utilized.16The World Health Organization promotes “rights-based transformation in mental health” and recognizes the Wildflower Alliance’s peer-based respite program as one of around 30 exemplary rights-based supports from around the globe. The WHO notes that policymakers and providers are calling for a “sea-change in mental health.” World Health Organization. Guidance on Community Mental Health Services: Promoting Person-Centred and Rights-Based Approaches. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240025707.

Case Study: CAHOOTS

The best-known example of civilian crisis response is CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets), a publicly-funded 911 response program run since 1989 by the White Bird Clinic in Eugene and Springfield, Oregon. When CAHOOTS is assigned a crisis call, they dispatch a two-person team consisting of a medic and a crisis worker. CAHOOTS response teams “deliver person-centered interventions and make referrals to behavioral health supports and services without the uniforms, sirens, and handcuffs that can exacerbate feelings of distress for people in crisis. They reduce unnecessary police contact and allow police to spend more time on crime-related matters.”17Beck, Jackson, Melissa Reuland, and Leah Pope. 2020. Case Study: CAHOOTS, Eugene, Oregon. Vera Institute of Justice. https://www.vera.org/behavioral-health-crisis-alternatives/cahoots Specifically, the teams provide services for:

- Crisis Counseling

- Substance Abuse

- Housing Crisis

- First Aid and Non-Emergency Medical Care

- Resource Connection and Referrals

- Suicide Prevention, Assessment, and Intervention

- Conflict Resolution and Mediation

- Grief and Loss

- Transportation to Services

Responders focus on listening, empathizing, stabilizing, and de-escalating, especially prioritizing a person’s basic needs like warmth, food and water, shelter, compassion, and a sense of trust. Peer responders are trusted and have an established reputation for meeting people’s needs from a stance of “unconditional positive regard,” so that even the most tense situations become much more manageable. CAHOOTS response is also often an entry point for residents in distress to receive more sustained therapeutic services, helping them to reach a point of stability and well-being and reducing the need for future emergency response. Out of an estimated 24,000 calls CAHOOTS responded to in 2019, they called for police backup only 311 times (1.3% of calls). According to CAHOOTS, no staff member has ever experienced a serious injury in over 30 years of responding to emergency calls.

75% of CAHOOTS responders identify as peers with lived experience of incarceration, substance use, neurodivergence, houselessness, and other forms of oppression. This level of peer participation is key to CAHOOTS’s success: because their staff positions are non-licensed paraprofessionals who get extensive on-the-job training, it’s easier for people from diverse backgrounds to get hired. Non-licensed crisis workers are also unable to involuntarily hospitalize community members, which greatly increases trust by residents in crisis.

The White Bird Clinic itself is run as a consensus-based collective with a diverse “stewardship council” made up of residents from the communities they serve. CAHOOTS thrives because of community trust, and that trust is built on providing care that is compassionate and consensual, unlike the punitive and coercive approaches that police and social workers rely on.

Impact on 911 Response and City Finances

In Eugene and Springfield, CAHOOTS handles 20% of 911 calls, despite having a budget that is only 2% of the police budget. CAHOOTS costs approximately $70/hour for emergency response, whereas police emergency response ranges from $200-300/hour. With a budget of only $2.2 million, CAHOOTS is estimated to directly save the municipalities $14 million. The program also saves hospital and health system costs by diverting emergency room visits and providing transportation as necessary. The Center for American Progress estimates that the CAHOOTS model could offer significant additional benefits and savings if they expanded their services to other low-risk non-emergency calls, diverting as much as 38% of 911 calls depending on local conditions.18Irwin, Amos, and Betsy Pearl. The Community Responder Model. Center for American Progress, October 2020. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/criminal-justice/reports/2020/10/28/492492/community-responder-model/

Civilian crisis response offers benefits to police, as well, reducing the burden that non-violent emergencies put on departments and improving community trust.19Roberts, Ronnie. “Hugging the Cactus.” Police Chief Magazine (blog), April 7, 2021. https://www.policechiefmagazine.org/hugging-the-cactus/. Increasingly since the advent of the 911 emergency call system, police have become the default mode of response to any call for help, expanding the scope and cost of policing and causing significant collateral damage in communities — especially among marginalized groups.

“We’re asking cops to do too much in this country… Every societal failure, we put it off on the cops to solve. Not enough mental health funding… loose dogs… schools fail… Policing was never meant to solve all those problems.”

Former Dallas Police Chief David Brown20Dennis, Brady, Mark Berman, and Elahe Izadi. “Dallas Police Chief Says ‘We’re Asking Cops to Do Too Much in This Country.’” Washington Post, July 11, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-nation/wp/2016/07/11/grief-and-anger-continue-after-dallas-attacks-and-police-shootings-as-debate-rages-over-policing/

Making It Happen in Greenfield

This proposal and the example of CAHOOTS are not an exact blueprint for a crisis response program in Greenfield. CAHOOTS helps us to see what’s possible when people with lived experience are supported and allowed to take on big responsibilities, but any program we build will have to be developed by the community and local partners, taking into account our local needs, capacities, and resources. We are blessed with local organizations who are recognized leaders in peer support and harm reduction who can help build a successful new program, as well as other much-needed community supports. Greenfield city government must welcome their leadership and help build their capacity, rather than crowding them out with harmful police-based interventions.

It’s time to convene these conversations. Together let’s take concrete steps towards shifting the paradigm of crisis response in our community.

Greenfield People’s Budget

June 2021

Further Resources

The following resources offer more detail on CAHOOTS and similar programs, implementation considerations, and comparisons with other response models.

- More about CAHOOTS – videos & articles

- The Wildflower Alliance’s Open Letter to the Mayor of Northampton, May 19, 2021

- Implementing Civilian Crisis Response – policy papers for municipal officials

- 1Neusteter, S. Rebecca, Maris Mapolski, Mawia Khogali, and Megan O’Toole. 2019. The 911 Call Processing System: A Review of the Literature as It Relates to Policing. Vera Institute of Justice. https://dataspace.princeton.edu/bitstream/88435/dsp01ms35tc556/1/911-call-processing-system-review-of-policing-literature.pdf

- 2Rogers, Michael S., Dale E. McNiel, and Renée L. Binder. “Effectiveness of Police Crisis Intervention Training Programs.” Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online 49, no. 1 (March 1, 2021). https://doi.org/10.29158/JAAPL.003863-19

- 3Westervelt, Eric. “Mental Health And Police Violence: How Crisis Intervention Teams Are Failing.” All Things Considered, September 18, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/09/18/913229469/mental-health-and-police-violence-how-crisis-intervention-teams-are-failing Osborne, Deon. “Cop Who Shot Woman with Mental Illness Gives Training to Campus Police.” The Black Wall Street Times, April 28, 2021. https://theblackwallsttimes.com/2021/04/28/cop-who-shot-woman-with-mental-illness-gives-training-to-campus-police/

- 4Vakharia, Sheila P. “‘Social Workers Belong in Police Departments’ Is an Offensive Statement.” Filter (blog), June 10, 2020. https://filtermag.org/social-workers-police-departments/ James-Townes, Lori. “Why Social Workers Cannot Work With Police.” Slate Magazine, August 11, 2020. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2020/08/social-workers-police-collaborate.html

- 5Evens, Philip. “Social Control and Values in Social Work.” Probation 19, no. 1 (March 1, 1973): 9–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/026455057301900103

- 6Davidow, Sera, for the Wildflower Alliance. “Open letter to the Mayor of Northampton,” May 19, 2021. https://wildfloweralliance.org/open-letter-to-the-mayor-of-northampton/ Vakharia, Sheila P. “‘Social Workers Belong in Police Departments’ Is an Offensive Statement.” Filter (blog), June 10, 2020. https://filtermag.org/social-workers-police-departments/ James-Townes, Lori. “Why Social Workers Cannot Work With Police.” Slate Magazine, August 11, 2020. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2020/08/social-workers-police-collaborate.html

- 7Angela Kimball, national director of advocacy and public policy for the National Alliance on Mental Illness, quoted in Minyvonne Burke, “Policing Mental Health: Recent Deaths Highlight Concerns over Officer Response.” NBC News, May 16, 2021. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/policing-mental-health-recent-deaths-highlight-concerns-over-officer-response-n1266935

- 8White, Mark. “Voters Want a Non-Police First Responder Agency for Addiction and Mental Health.” Data For Progress, June 11, 2020. https://www.dataforprogress.org/blog/6/11/voters-want-non-police-first-responders

- 9“Community Forum Recommendations,” shared with Greenfield councilors in December 2020

- 10Tim Black, CAHOOTS, Interview with Northampton Policing Review Commission, March 10, 2021; Rachel Bromberg, Reach Out Response Network, Interview with NPRC, January 5, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a1VP-DsHEs0

- 11Davidson, Larry, Chyrell Bell Amy, Kimberly Guy, and Rebecca Miller. “Peer Support among Persons with Severe Mental Illnesses: A Review of Evidence and Experience.” World Psychiatry 11, no. 2 (June 2012): 123–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.05.009

- 12Quoted by Sera Davidow for the Wildflower Alliance. “Open letter to the Mayor of Northampton,” May 19, 2021. https://wildfloweralliance.org/open-letter-to-the-mayor-of-northampton/

- 13Sundaresh, Ram, Youngmin Yi, Brita Roy, Carley Riley, Christopher Wildeman, and Emily A. Wang. 2020. Exposure to the US Criminal Legal System and Well-Being: A 2018 Cross-Sectional Study. American Journal of Public Health 110: S116-S122. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305414

- 14Irwin, Amos, and Betsy Pearl. The Community Responder Model. Center for American Progress, October 2020. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/criminal-justice/reports/2020/10/28/492492/community-responder-model/ Camplain, Ricky, Carolyn Camplain, Robert T. Trotter II, George Pro, Samantha Sabo, Emery Eaves, Marie Peoples, and Julie A. Baldwin. 2020. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Drug- and Alcohol-Related Arrest Outcomes in a Southwest County From 2009 to 2018. American Journal of Public Health 110: S85-S92. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305409

- 15Davidow, Sera, for the Wildflower Alliance. “Open letter to the Mayor of Northampton,” May 19, 2021. https://wildfloweralliance.org/open-letter-to-the-mayor-of-northampton/

- 16The World Health Organization promotes “rights-based transformation in mental health” and recognizes the Wildflower Alliance’s peer-based respite program as one of around 30 exemplary rights-based supports from around the globe. The WHO notes that policymakers and providers are calling for a “sea-change in mental health.” World Health Organization. Guidance on Community Mental Health Services: Promoting Person-Centred and Rights-Based Approaches. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240025707.

- 17Beck, Jackson, Melissa Reuland, and Leah Pope. 2020. Case Study: CAHOOTS, Eugene, Oregon. Vera Institute of Justice. https://www.vera.org/behavioral-health-crisis-alternatives/cahoots

- 18Irwin, Amos, and Betsy Pearl. The Community Responder Model. Center for American Progress, October 2020. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/criminal-justice/reports/2020/10/28/492492/community-responder-model/

- 19Roberts, Ronnie. “Hugging the Cactus.” Police Chief Magazine (blog), April 7, 2021. https://www.policechiefmagazine.org/hugging-the-cactus/.

- 20Dennis, Brady, Mark Berman, and Elahe Izadi. “Dallas Police Chief Says ‘We’re Asking Cops to Do Too Much in This Country.’” Washington Post, July 11, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-nation/wp/2016/07/11/grief-and-anger-continue-after-dallas-attacks-and-police-shootings-as-debate-rages-over-policing/