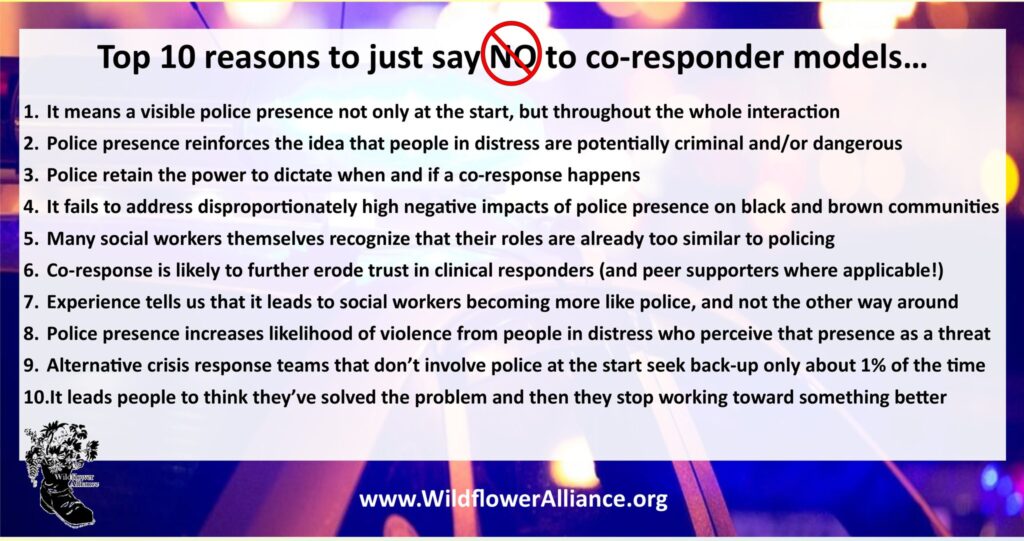

Definition: “Co-responders” are social workers who accompany police responding to emergency calls, also called “police-embedded clinicians.” These programs have existed for decades, but law enforcement agencies are increasingly promoting co-response in the face of widespread criticism of police. The Greenfield People’s Budget, like many community organizers and mental health professionals across the nation, are opposed to the co-response model.

Q: A co-responder seems like a good, incremental step towards a better system for dealing with emergencies. Why are you opposed to incremental change?

A: At the surface level, Co-responders can seem like an improvement, but they are not an incremental change towards some other system that offers better mental health care. By keeping police involved in mental health calls, these models in fact represent a significant expansion of policing. Co-responder models serve to legitimize police being involved in more and more non-violent life situations. Police also retain ultimate authority over how the team responds to a call, despite their frequent claims of following the lead of the co-responder. Recall that co-responders are generally one clinician surrounded by police and police culture, responding to calls at the discretion of the police. A single clinician cannot take on the entrenched, punishment-focused culture of police officers and their unions, and no clinician that tried would get the job or be able to keep it.

Co-responder programs have been around for decades, and despite claims by police they are not new or innovative. Because co-responder models have such a long track record, we have plenty of evidence showing the harms of such programs. The mere presence of police causes a range of practical and ethical dilemmas for care providers. Adding social workers to police response does not guarantee compassionate care, increase community trust, or rule out coercive outcomes. Instead, it pulls social work further away from care and more towards policing and punishment. This is why many social workers and even law enforcement professionals are opposed to co-response models, yet many police and politicians promote these programs to advance their own interests.

Furthermore, experience has shown that co-responder programs are not an incremental change: Proponents of co-responder programs do not outline any concrete path from co-response to non-police response. For them, police-based response is the goal, not a step towards something else. In practice, co-responder programs have become a key tool for preventing non-police programs from becoming established. Because police generally retain control over emergency dispatch even when non-police programs are created, police have steered calls away from non-police programs and towards co-responder programs, in order to undermine non-police programs they see as politically threatening. Public officials have also offered generous on-going funding for co-responder programs while consistently underfunding non-police programs, setting them up to fail.

Q: Aren’t police important for keeping civilian responders safe?

A: Police assume by default that most situations are dangerous. Police training emphasizes the idea that they can be ambushed or attacked at any time. Much of the reason they assume people in personal crisis are dangerous is that police regularly witness these situations escalate into violent struggles, but police themselves are a primary source of escalation and violence. Cops’ reputation precedes them, and officers shouting, acting aggressively, and threatening an agitated person with their weapons is a proven strategy to make a difficult situation spiral out of control.

Police counter that they have special training in mental health de-escalation, usually Crisis Intervention Teams training. CIT training has changed officers’ attitudes and their assessment of their own skill in handling calls, but there’s zero evidence it has improved outcomes: CIT training does not reduce arrests, use of force, or citizen injuries. Officers proficient in CIT, some of them even CIT trainers, have killed people in mental distress. This is why, following the federal CDC, CIT trainers themselves are opposed to co-response:

“The presence of law enforcement at a mental health crisis event implicitly defines the situation as a potentially dangerous and criminal matter. This can become real in its consequences, as the mere presence of police can escalate the person in crisis, particularly if they have a history of trauma.

“It is important to note that most people experiencing a mental health crisis are not violent nor are they engaged in criminal behavior. They report that having police involved is stigmatizing and increases trauma at a time when they feel extremely frightened and vulnerable. Furthermore, the negative impact of police involvement is disproportionately experienced in communities of color, who are demanding alternatives to law enforcement response. Simply putting a clinician in a police car does not address these concerns.”

CIT International, “Why doesn’t CIT International promote the embedded co-responder model?”

Non-police crisis response units are able to respond to crisis calls with much less risk of escalation. The well-known CAHOOTS program, in Eugene, Oregon, has responded to hundreds of thousands of calls over more than 30 years with very few injuries to responders or the people they’re helping. They only very rarely call the police, either. As their director said, “It’s our experience that folks in crisis just aren’t dangerous.”

Q: Should we just send a social worker team to mental health calls?

A: The best response to a mental health emergency is peer support workers and medics, not licensed clinicians. Peer counselors combine lived experience and expert training to help people in crisis get the care they need in a manner they can trust, rejecting coercive and punitive approaches (such as involuntary hospitalization) in favor of therapeutic peer support practices. However, peer support workers cannot effectively offer consensual, person-centered care in bureaucratic agencies (like CSO or ServiceNet) that collaborate closely with law enforcement, rely heavily on coercive interventions, treat their own employees terribly, and consistently prioritize profit and legal liability over patients’ well-being. Coercive care is policing by another name with similar devastating results for many clients. Unfortunately, these large institutional care providers are dominant in the existing mental/behavioral health care system.

We cannot provide appropriate care to people in crisis if we limit ourselves to a false choice between police-based interventions or profit-based interventions.

Q: Isn’t it good that the police are involving a “community organization” in their work?

It is not helpful to call a bureaucratic, profit-oriented health agency a “community organization.” Just because they have 501(c)3 tax status does not mean they are directed by community values rather than acquiring lucrative state contracts.

Employees at CSO (and ServiceNet, and others) have been outspoken about demeaning working conditions and pay, lack of support for staff, and the poor quality of care they are able to provide as a result. Clients of these agencies also regularly complain about their treatment by the agencies, not least because the providers regularly call on police and lean heavily on coercive interventions such as involuntary hospitalization and forced psychiatric medication.

Non-profit executives, police, and politicians all play the same language games, slapping trendy labels like “trauma-informed” and “peer-based” on the same old institutional, coercive, profit-driven models of care. Referring to social service agencies as “community organizations” is a deception designed to distract from the fact that these agencies’ only real customer is the state. The product they offer: providing “care” in the cheapest possible way with no regard for the human costs.

Q: What about domestic violence? These calls are dangerous for responders and police are helpful in these situations.

A: If survivors choose to call the police as their strategy to be safe, we honor that choice. We must also acknowledge that most victims of abuse never call the police. Why not?

- Because police don’t stop abuse. Most often victims’ primary goal is not to have their abusive partner arrested–it’s to have them stop abusing them. When police do arrest an abuser, they are usually sent right back home and forced to attend and pay for coercive therapy programs. If abusers are jailed, the cycle of harm is perpetuated setting the stage for more trauma and more abuse later.

- Because police harm survivors. Survivors of abuse are often accused of crime by police, and they are often abused or assaulted by police. Calling the police also means that DCF is going to get involved in your family, with a likely result that you will lose custody of your children and suffer additional punitive sanctions or prison. This system of family policing regularly punishes mothers for “failing to protect” their children from their abusive partners.

Co-response programs do not address these harms. In order to help the majority of victims who are not calling for help right now, we need a completely different framework–one that offers justice for victims and stops the cycles of harm that lead to abuse in the first place. Policing and incarceration play a central role in that cycle of harm and abuse. We do not claim that non-police crisis response programs like CAHOOTS are a clear fix for domestic violence emergencies, either. The message from survivor advocates is clear: there is no easy fix, no one-size-fits-all solution for helping survivors, but we have to aim to reduce harm. For this reason we cannot let policing and prison solutions be the focus of our responses to abuse.

Further reading

- NPR: Mental Health and Police Violence: How Crisis Intervention Teams Are Failing

- Wildflower Alliance open letter to the Mayor of Northampton

- Greenfield People’s Budget proposal for civilian crisis response in Franklin County

- Mariame Kaba’s Zine What About the Rapists? on sexual violence and police abolition

- Andrea Ritchie’s Police Responses to Domestic Violence: A Fact Sheet